Beware of Marxists in French Clothes

- In the world of economists, Thomas Piketty has been lauded as an overnight rock star. But does he really have anything new to say?

- Today, Nicholas Vardy explains why Piketty’s financial economics are hardly worthy of acclaim.

Last week, I saw French economist Thomas Piketty introduce his new book, Capitalism and Ideology, at the London School of Economics.

Few Americans have ever heard of Piketty.

But in the world of economists, Piketty’s earlier book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2014, turned this obscure French academic into an economic rock star overnight.

I was excited to find out what the fuss was all about.

Piketty began his talk with a history of economic inequality going back to the French Revolution starting in 1789.

He ended it with all too predictable left-wing policy prescriptions to right the injustices of the world.

The gist of these prescriptions is best summarized by the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s 1998 book: Eat the Rich.

In the end, Piketty’s talk left me disappointed.

I had come to absorb the insights of the greatest economist of his generation. But I left feeling I had just attended a Bernie Sanders political rally.

Piketty’s View of Economic Inequality

Piketty’s view of capitalism is familiar to any college freshman who has studied Karl Marx in a Western civilization course.

Capitalism is dominated by those who are ruthless enough to get rich. And it is run by later generations lucky enough to be born into inherited wealth.

This concentration of wealth highlights the fundamental contradiction in capitalism.

Piketty explains this contradiction with a simple equation.

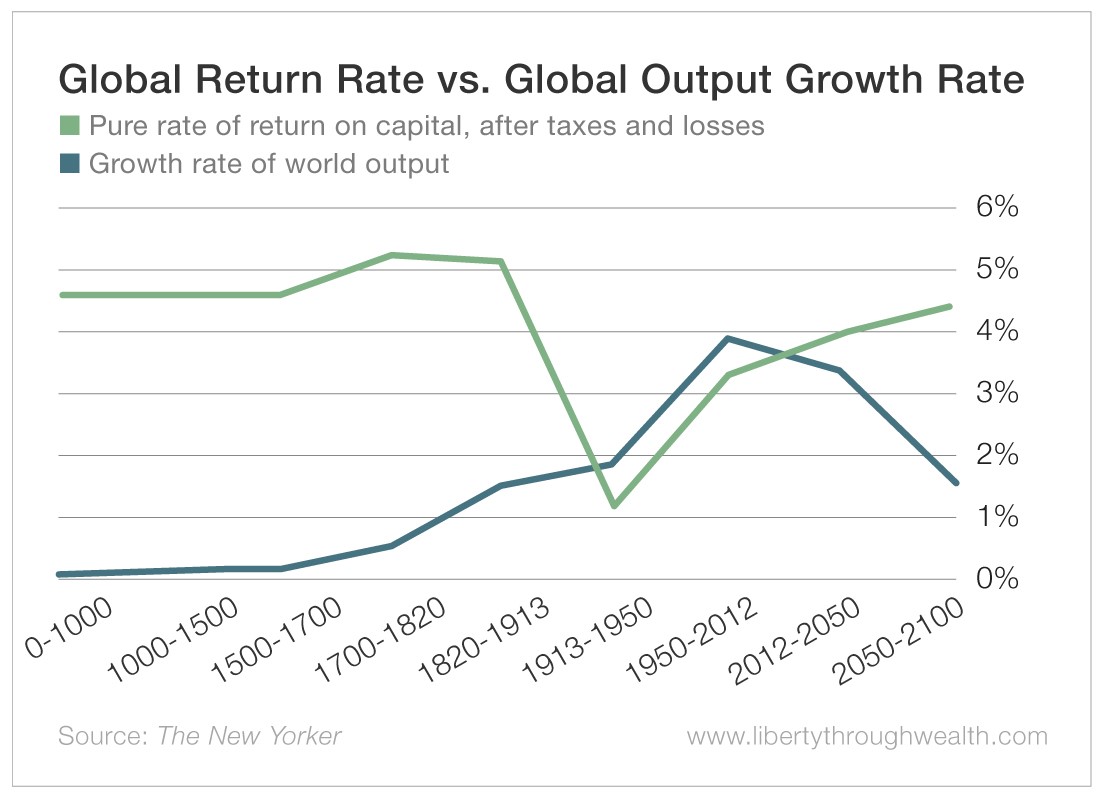

Over the course of history, capital earns a 5% rate of return on average. Piketty calls this r.

Income from labor grows at the rate of overall GDP. This is always less than 5%. Piketty calls this g.

Because r > g, the rich will always get richer.

When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of economic growth, inequality will inevitably rise.

The tyranny of inherited wealth was upended only by the destruction of capital during the First and Second World Wars.

Why Piketty Became a Rock Star

The mainstream media hailed Piketty’s first book as one of the most important economics texts ever written. They compared it to Marx’s Das Kapital and John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

I now understand why.

Piketty essentially offers a Marxist critique of a class-ridden society, with a particular place in hell for the unearned wealth of a hereditary elite.

But before Piketty burst onto the scene, Marxists had a problem.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, even academic Marxists have had to stop calling themselves Marxists. Enter Piketty, who offered a Marxist critique of capitalism, without having to invoke the “M-word.”

Piketty makes no secret of this.

After all, he writes doorstop-thick books with the word “Capital” in them with the intention of evoking an association with Marx.

Piketty’s Prescription

Piketty’s policy prescriptions are predictable.

They include an income tax rate of at least 80% and an elimination of inheritances through confiscatory inheritance tax rates of up to 90%.

These taxes would fund the allocation of 120,000 euros to all young people under 25. (A surefire winner among an audience of London School of Economics students!)

More broadly, Piketty argues for a new “participatory” socialism.

Picketty’s version of socialism – apparently unlike every single other version that has been tried – is founded on “an ideology of equality, social property, education, and the sharing of knowledge and power.”

Yeah, right.

Tell the citizens of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union who had to endure decades of political oppression in the name of socialism.

No one ever climbed the Berlin Wall to escape into East Germany.

Piketty also wrongly assumes that capitalism today is dominated not by the founders of new companies but by the grandchildren of the super-elite.

The reality is quite different.

In 1984, less than half the people on the Forbes 400 were self-made.

In 2018, 67% of the Forbes 400 had created their own fortunes.

For someone like Piketty who prides himself on grounding his arguments in empirical data, this is an embarrassing mistake.

I expected him to be a compelling, original thinker.

After all, former Harvard President and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers called Piketty’s first book “a Nobel Prize-worthy contribution.”

Instead, what I saw in Piketty was a just a rebranded Marxist.

And that alone is hardly worthy of any prize.

About Nicholas Vardy

An accomplished investment advisor and widely recognized expert on quantitative investing, global investing and exchange-traded funds, Nicholas has been a regular commentator on CNN International and Fox Business Network. He has also been cited in The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Newsweek, Fox Business News, CBS, MarketWatch, Yahoo Finance and MSN Money Central. Nicholas holds a bachelor’s and a master’s from Stanford University and a J.D. from Harvard Law School. It’s no wonder his groundbreaking content is published regularly in the free daily e-letter Liberty Through Wealth.